On Malaysia’s Independence Day today, my thoughts turn to a road trip I took with my dad in 2010. We drove up from Kuala Lumpur to Menglembu, so that he could show me the house where he spent the first eighteen years of his life. Back then, I was helping Dad write his memoirs. My sister had handed me her notes and the eleven pages she had written. My job was to complete the rest.

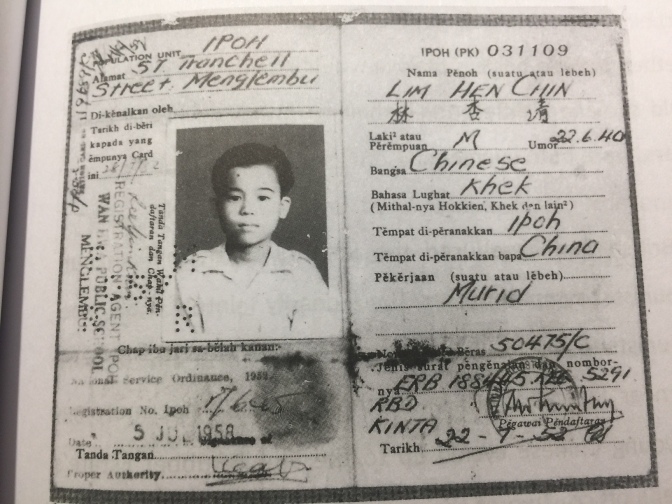

Dad’s first Identity Card (IC) was issued in 1952, when he was 12 years old. The card itself is a curious mix of languages: English, Malay, Chinese. The British introduced the IC to fight communism and it was a possible precursor to some sort of citizenship document in anticipation of the day when Malaya would be granted independence.

Dad’s address is listed as 57, Tranchell Street, Menglembu. In 2010, when Dad pulled off the North-South Highway, his memory guided him. Tranchell Road is no longer on the map. It has been renamed.

Looking at Google Maps this morning, I think Tranchell Road is somewhere in the cluster of roads renamed Jalan Menglembu Timur 1 to Jalan Menglembu Timur 16. Very long names. A tad unwieldy. I understand why the roads have been renamed – to name and to rename is the prerogative of the ruling power – but I cannot help feeling that something has been lost in the process, some enigma, some history, some story.

Paul Kelly wrote in The Australian yesterday that the current debate over the inscription on Captain Cook’s statue is really about ‘how European Australian and indigenous Australia are going to reconcile on this continent given their competing cultures and histories.’ He warned against revising history because there will be no end and it will leave both sides depleted.

Revising history is difficult and dangerous. But revisiting history is not. I think we should revisit history many times, preferably from different points of view, and hopefully, each time, we gain a better understanding of what happened, a more nuanced, more accurate version of what happened and why.

I think it is crucial we pay attention to the telling and retelling of history because history confers legitimacy. It shapes understanding. It speaks to what we allow and forbid, what we love and hate, and who we allow ourselves to become.

I am so glad I embarked on that road trip with Dad. I discovered things I would never have otherwise discovered. It took three years to write the book, Fish in the Well, which we self-published in 2013. I hope to make it available shortly as an eBook. Please subscribe if you would like to hear more.