When I was a little girl, my family drove from KL to Ipoh so often that I memorised the small towns along the way: Slim River (half-way point), Bidor (eat duck noodles in double-boiled herbal soup), Tapah, Kampar, Gopeng, Ipoh.

Some of the one-street towns appeared as a brief anomalies that whizzed past my backseat window. Those concrete shops looked as if they had fought valiantly against the rainforest for their place and won.

By contrast, towering limestone cliffs flanked the approach to Ipoh. The challenge in our little car was to be the first to spot the Mercedes Benz sign high up on the hills. It indicated that we had arrived.

The Ipoh of my childhood was for holidays and extended time with my cousins. My grandparents’ living room had a concrete and glass aquarium, and portraits of my grandparents and great-grandparents on either side of a towering grandfather clock. At some point during every Chinese New Year, my mother or one of my aunts would say, ‘All line up and kiss Gong Gong.‘

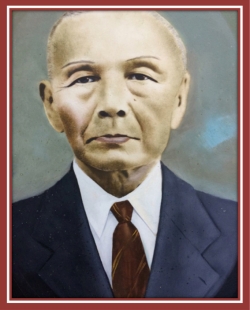

My grandfather was practically bald, apart from a comb-over. He wore slip-in suede shoes and walked in a shuffling gait. He would be guided to a chair, from which he received kisses and presented ang pows.

I remember the feel of his scratchy stubble as I leaned forward to peck him on the cheek. With good humour, he would give me a red packet as a hand-coloured version of his younger self smiled from a portrait photograph on the wall.

The going rate, for as long as I can remember, was ten Ringgit. And so, my image of him as a wealthy businessman, who drove the first Mercedes Benz in Ipoh (so I have been told), appeared to me fully formed, set in concrete, so to speak.

My grandfather, Loh Mee Loon, owned and operated Ban Loong. Initially, he sold all sorts of weighing scales and was also a tinsmith. His shop stood in the centre of Old Town, Ipoh. He had bought it 1926.

His father, Loh Siew San, had migrated from China and settled in Sungai Siput, a small town north of Ipoh. I try to imagine the kind foresight, self-belief and courage that compelled my grandfather, a small town migrant kid, to stretch himself to purchase a commercial property in the tin-mining capital of Malaya when he was only twenty-three years old.

In those days, migrants and mail came by long ship journeys. A husband who had sent for his wife might have relocated by the time she arrived. To address this problem, my grandfather opened his shop to new Chinese migrants. Ban Loong provided temporary accommodation and food in exchange for labour and soon became a community hub.

Then came the destruction of World War II. Bombs rained from Japanese planes. After the war, my grandfather saw an opportunity in the destruction and expanded his business to hardware supply. Business prospered as the townspeople began rebuilding.

In 2015, when the hardware business was no longer viable, grandson Ir. Loh Ban Ho decided to commit himself to preserving the building. It is fortuitous that Ban Ho is a civil and structural engineer. The old colonial building required new engineering solutions. To meet fire safety standards, the wooden staircase and wooden first floor were dismantled. A steel framework was constructed within the old walls to carry the weight of a new concrete slab.

‘We basically built a new building within the old one. It was three times more expensive than building a new shop, but we didn’t want to tear down the original structure,’ said Ban Ho.

Fittingly, the restored shop now is Ban Loong Hotel, a testament to the foresight, can-do attitude and hospitality of my grandparents’ generation.

Next Friday: an interview with Tricia Rushton that almost made me cry. She’s a very busy woman, who has worked on projects as diverse as building stronger families, Indigenous Financial management and refugee support.